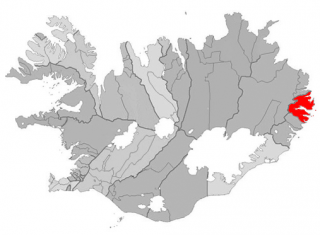

American-writer, Delaney Nolan, recently travelled to the east of Iceland to spend time in Stöðvarfjörður, where she discovered an expansive world of art and culture amongst a village on the fringes of descent.

American-writer, Delaney Nolan, recently travelled to the east of Iceland to spend time in Stöðvarfjörður, where she discovered an expansive world of art and culture amongst a village on the fringes of descent.

In East Iceland, near Egilsstaðir, Skúli Gunnarson runs the Skriðuklaustur Culture Center, a beautiful little college and the former home of Gunnar Gunnarsson, one of Iceland’s most famous authors. Year-round, one or two artists take up residency in the cottage’s apartment, where they concentrate on their chosen discipline for three to eight weeks. Painters, composers, and writers from across the world have all spent time there, drawing from the beautiful, secluded environment. In an area where many small towns have found themselves dwindling to nothing due to the changing face of the fishing industry, the culture center may be one example of what some are calling the “residency industry”—an expansion of art-centered programs that draw in foreign artists to areas that don’t normally benefit from Iceland’s crucial tourism sector.

“This town used to have hundreds of people,” says Gunnarsson as we drive through the quiet seaside village of Stöðvarfjörður. We’re miles from the next town, in the bay of a scenic fjord. “Now they have a problem with the age of the population, the population getting older. Families can’t stay when there are just one, two other kids the same age as their child. There are schools with just thirty students in them, in the entire school.”

Stöðvarfjörður now has about 200 residents, and most young people have left. The community youth hall has closed due to disuse. He explains that some artists live there– Rósa Valtingojer, a textile and ceramics designer, and Zdenek Patak, a well-known graphics designer. Together, they’ve founded HERE, a creative center housed in a former fish factory. There’s talk, too, of starting up a residency program. In a shrinking coastal town with little industry to speak of, it may be the best plan for Stöðvarfjörður’s survival.

Iceland depends on the fishing industry, an industry that accounts for about 25 percent of gross domestic product. Fishing and its supporting industries account for about 15% of jobs in the country. This industry was instrumental in Iceland’s recovery from its economic collapse in 2008.

However, when fish population began to decline due to overfishing in the 1980s, Iceland introduced ITQ (Individual transferrable quotas) to regulate the fishing rate. With quotas reduced and fleets growing more efficient, many fishermen lost their jobs, and fishing villages suffered. Thus, due to these necessary measurements for resource management, the industry that used to support small coastal towns has become more centralised, and villages are shrinking. The rise of heavy industry, such as aluminum smelting, has also drawn workers and families to more populated areas. In a country like Iceland—the most sparsely populated country in Europe—there’s plenty of space for isolated seaside towns like Stöðvarfjörður. But as the face of the economy changes, they can be left stranded.

The Skriduklaustur Institute is just one example of the kind of organisations which have begun to appear as locals search for new ways to support their economy. Dozens or artist residency programs have opened their doors in the last few years. With a striking, singular landscape and plenty of room for solitude, it’s no wonder that Iceland become an increasingly popular destination amongst artists of all kinds. These residencies and fellowships are managed in different ways—in some, accommodation is provided along with a stipend for meals and travel expenses. On the other end of the spectrum, there are residencies for which artist receives no stipend, and instead pays a residency fee, essentially renting out a space to do work in.

Nowhere is this change more symbolic than at HERE, the culture center in the old fish factory in Stöðvarfjörður. When the factory closed due to declining revenue, it sat unused for decades, until HERE’s founders decided to re-open it in an effort to make the town self-sustaining once more. They say their goal is to enable people from the surrounding area to work on creative projects, but it’ll also be open to outsiders for residencies and workshops

Gunnarsson acknowledges that it may not be the rise of a new, wide-reaching industry, but “This wave of residencies popping up in small towns around Iceland is a good thing,” he says. “It doesn’t help the economy directly, but it brings new streams of thinking into the towns, connections to the world. The fertile creativity of the artists can help the societies to go out of the box.”

All in all, it’s a smart way for Icelanders to invest in one resource that is copious in their country—space and natural beauty. It’s also a way to promote cross-cultural exchange, celebrate Iceland’s own art scene, and boost tourism without selling a caricature of their country.

Delaney Nolan is a fiction writer, who has been previously published in Huffington Post, Grist, PANK, amongst others. She is the winner of the 2012 Ropewalk Press Fiction Editor’s Chapbook Prize; a Sozopol fiction fellow; and a Bread Loaf work-study scholar – delanticnolan@gmail.com.